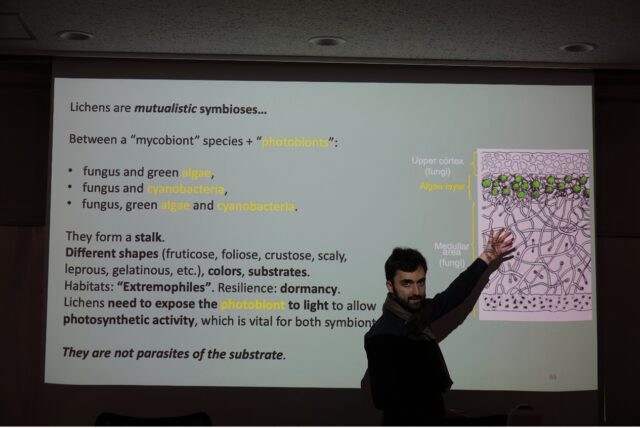

On Tuesday, 8th April, from 17:00 to 18:30, Mr. Vincent Zonca’s lecture titled Thinking with Lichens: A Transdisciplinary Approach, from the Anthropocene to the Concept of Symbiosis was held at the EAA seminar room, Komaba Campus, University of Tokyo. With discussant Dr. Rui Matsuba from Rissho University and moderator Dr. Futoshi Hoshino from EAA, University of Tokyo, Mr. Zonca presented a transdisciplinary inquiry into how lichens can inspire new ecological, political, and philosophical understandings in the Anthropocene era. The lecture, rooted in his book Lichens: Toward a Minimal Resistance, made a thought-provoking experience for all who attended by the speaker’s brilliant presentation and the incisive discussion session.

The term “Anthropocene” refers to an epoch marking a new era when human activity began significantly impacting the Earth’s climate, geology, and ecosystems through industrialization, urbanization, pollution, climate change, and more. Moreover, a worldwide pandemic has compelled us to rethink how we should behave when interacting with each other, let alone with nature. In the lecture, Mr. Vincent Zonca proposed that lichens can act as catalysts or crystallizers of a new way of thinking or a connection to other living beings. While often overlooked in daily life, lichens are gaining symbolic importance in recent intellectual, artistic, and environmental discourses. Mr. Zonca quoted renowned thinkers and philosophers, including Pierre Gascar and Donna Haraway, who perceive lichens as metaphors for ecological resilience, political resistance, and alternative forms of postmodern community. Nevertheless, Mr. Zonca pointed out that lichens are omnipresent yet culturally invisible in Western culture. Not until the mid-19th century did science define lichens as a symbiotic entity, as their invisibility was partly due to their ambiguous classification throughout history, shifting between moss, algae, and fungus. Lichens were long associated with disease and unappealing, which can be seen in their absence from classical European art. In contrast, Mr. Zonca noted that Japanese, Canadian, and Arctic traditions have long appreciated lichens both visually and ecologically.

Mr. Zonca illustrated how cultural attitudes influence ecological awareness by comparing lichenophilic cultures, such as those in northern Canada and Japan, with mycophobic tendencies in France. In Canada, Inuit and indigenous artists weave lichens into rawhide installations and use lichen-dyed gelatin in multimedia work, highlighting that lichens are integral to ecosystems and Indigenous livelihoods, symbolizing interconnectedness between humans, animals, and landscapes. As part of nature, humans can never overestimate their superiority over the natural world, nor individual themselves. Regarding ways of living akin to lichens, Mr. Zonca indicated that lichens embody the concept of “symbiosis” both physically and metaphorically, challenging notions of individualism, purity, and fixed identity. By examining lichen’s structure, Mr. Zonca suggested that lichens—organisms composed of multiple species—offer a model for queer theory, posthumanism, and the concept of symbiotic subjectivity.

In the discussion that followed, Dr. Matsuba first reflected on his personal encounter with lichens at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo, which led him to contemplate the relationship between humans and lichens. Both are scattered across the Earth, and their similarities raised questions about how non-human entities challenge traditional notions of individualism and open up discussions on subjectivity. Dr. Matsuba cited a key concept that emerged in 19th-century biology and is mentioned in Mr. Zonca’s book: “Every bios is a symbios”. This challenges binary frameworks such as naturalism or globalism and offers new philosophical inspiration. The way lichens live can serve as a model for resisting political oppression and can be seen as representing an anarchic and transformative form of existence.

Based on these reflections, Dr. Matsuba posed two philosophical questions concerning mortality, freedom, and coexistence within a symbiotic framework. The first question was: “How can we accept individual death?”. For lichens, living through the death of others is natural. But for humans, death remains a profound existential issue with no universal solution has been found. While death reveals the inescapability of humanism and individualism, learning to accept individual mortality becomes a fundamental concern. The second question is:“How can we reconstruct freedom with coexistence?”. In contemporary theories of political justice, when values such as life or death are violated, people often seek judgment and assign blame to individuals. If we were to adopt a lichen-like way of living, how should we rethink legal systems that are founded on the idea of individual human freedom and dignity—especially when such a shift might risk undermining those very principles?

In response, Mr. Zonca acknowledged that although lichens have no intrinsic ethics or politics, they serve as mirrors through which humans can project aspirations for non-hierarchical, interconnected modes of living. He cautioned against romanticizing nature through anthropocentric metaphors but affirmed that lichens have the capacity to provoke critical reflection on our place in the web of life. Mr. Zonca concluded by advocating for a shift in both anthropology and ecology—from a human-centered worldview to one that includes all forms of life. By “thinking with lichens,” we can begin to imagine more inclusive, adaptable, and sustainable futures grounded in coexistence rather than dominance.

Report by: Christo Lau Sze Ho (EAA Research Assistant)

Photos by: Annabel Wei,Yun-Dian (EAA Research Assistant)